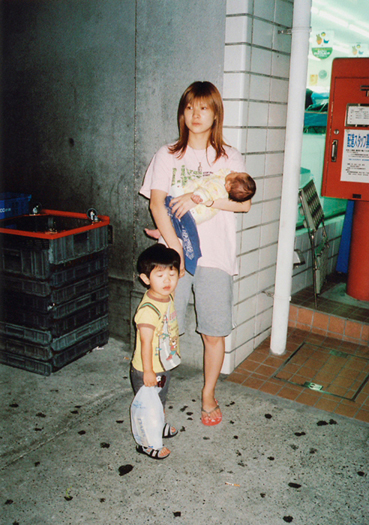

LOVESODY is a photographic work that traces a temporary and unstable relationship between the artist, a young mother, and her two children. What is recorded here is not intimacy or affection themselves, but the condition in which such closeness fails to fully take shape, remaining in constant fluctuation. The relationship lasts for only six months, yet within that brief period the artist’s position never stabilizes. He appears at times as a partner, at times as a parental figure, and at others recedes to a position closer to that of a child. None of these roles settles into a definitive identity.

In this work, proximity does not necessarily produce understanding or stability. Care and desire, dependency and distance, are not clearly separated but coexist simultaneously.

The camera’s gaze refuses to settle into a single position and offers no moral or emotional resolution. Intimacy is neither affirmed nor denied; it is presented as a condition that remains inherently unsustainable.

Structurally, LOVESODY can be situated within the lineage of the photographic diary in Japanese photography. Yet it resists the confessional certainty and narrative closure often associated with that tradition. While the work is bound by a clear timeframe, what it presents is not a completed experience but an ongoing process in which relationships are continually negotiated.

Domestic space appears not as a site of stability, but as one in which roles and distances are provisionally reconfigured.

LOVESODY is the earliest work in the artist’s practice. At the time of its production, the artist himself was also in a state in which the contours of daily life, social roles, and artistic values had yet to solidify. That uncertainty is inscribed in the work, overlapping with and reflected through the instability of the relationship it depicts.

In this sense, LOVESODY is less a document of a particular relationship than a record of a condition in which relationships persist without settling. In a time when social structures such as family, partnership, and responsibility no longer align neatly, the work presents intimacy as something generated under constant tension, without resolution or sentimentality.